- Visit Us Safely

- Opening Hours

- Getting Here

- Admission and Tickets

- Exhibitions

- Virtual 3D Tour

- Kunstkamera Mobile Guide

- History of the Kunstkamera

- The Kunstkamera: all knowledge of the world in one building

- Establishment of the Kunstkamera in 1714

- The Kunstkamera as part of the Academy of Sciences

- The Kunstkamera building

- First collections

- Peter the Great's trips to Europe

- Acquisition of collections in Europe: Frederik Ruysch, Albert Seba, Joseph-Guichard Duverney

- The Gottorp (Great Academic) globe

- Siberian expedition of Daniel Gottlieb Messerschmidt

- The Academic detachment of the second Kamchatka expedition (1733-1743)

- 1747 fire in the Kunstkamera

- Fr.-L. Jeallatscbitsch trip to China with a mission of the Academy of Sciences (1753-1756)

- Siberian collections

- Academy of Sciences' expeditions for geographical and economic exploration of Russia (1768-1774)

- Research in the Pacific

- James Cook's collections

- Early Japanese collections

- Russian circumnavigations of the world and collections of the Kunstkamera

- Kunstkamera superintendents

- Explore Collections Online

- Filming and Images Requests FAQs

The Anatomical Theatre

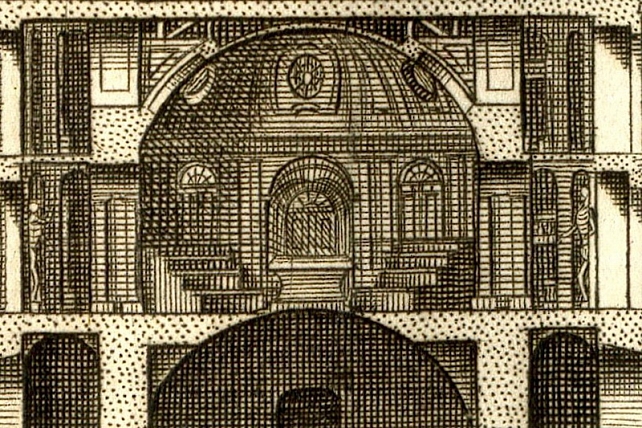

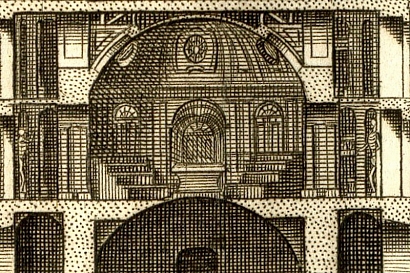

First anatomical theatres appeared in Europe in the 15th- 16th centuries, though people had always been interested in the organization of their bodies. But since ancient times, there existed religious bans on corpse dissections. It is believed that the first wooden collapsible anatomical theater, which could be transported, was built in Padua in the 15th century. A permanent anatomical theatre came into being at the University of Padua in 1594. Its height was 13 m, and up to 250 spectators could be accommodated in the auditorium shaped like a cone.

In 1597, Dutch professor Petrus Paaw (1564–1617) put into use a permanent anatomical theatre in Leiden. He decorated it with skeletons of birds, animals, and a Latin aphorism “Death is the line that marks the end of all”. For public anatomical dissection they were using corpses of criminals; their wickedness sort of justified such utilization. The ceremony of dissection of a body was backed by music (a small orchestra or one or two flutists); perfumes were diffused in the auditorium and big candles illuminated the autopsy table and the praelector in ceremonial attire. The autopsy procedure was gradually turning into a solemn performance the purpose of which was education and admonition of the spectators in the spirit of vainness and transience of life, an idea so typical for the baroque epoch. The edifice of the theater began to be used not only for the intended purpose but was turning into a museum, lecture hall, a place for discussions and experiments. An experienced and skillful praelector endeavored to create an elated theatrical atmosphere. Dutch anatomist Frederik Ruysch (1638–1731) was particularly famous for his mastership; in the course of 30 years, he had been performing autopsies in the Amsterdam Anatomical Theatre which not only physicians from many European countries but also diplomats and nobility were attending. Anatomical theatres turned into a specific phenomenon of the 17th century, when the cultural paradigm had been built in such a way that a lesson of anatomy, namely, autopsy of a human body, was presented as a gracious public event. On the one hand, they promised the public to show what Nature was giving to each person, and on the other hand, this was demonstrated on the corpse of a criminal, a “villain”, which served as a reminder of sin.

First encounter of Russians with an anatomical theatre occurred in Leiden in the course of the Grand Embassy to Holland in 1698. The Tsar attended lectures on anatomy there, took lessons from Frederik Ruysch, and was able to appreciate this new for Russians science as the foundation of surgery. That was why in affiliation with the hospital founded in Moscow in 1706, the first Russian anatomical theatre was established by a Tsar’s edict. Physician Nicolaas Bidloo (1670–1735), invited to Russia from Holland, took charge of it, and Peter I “was frequently present at the dissections of dead bodies” and acquired “skills of methodical dissection of those.”

The anatomical theatre affiliated with the Academy of Sciences was established in St. Petersburg in the unfinished palace of Tsarina Praskovia Fyodovna; it started functioning in 1726. Professor Johann Georg Duvernoy (1691–1759) was invited from Germany to work in it. He came from the University of Tubingen along with his student Josias Weitbrecht. Duvernoy was performing autopsies of not only bodies sent here from the Police Master’s and Medical Chancelleries but also bodies of rare dead animals which had lived at court’s account, namely, an elephant, a lion, and a leopard.

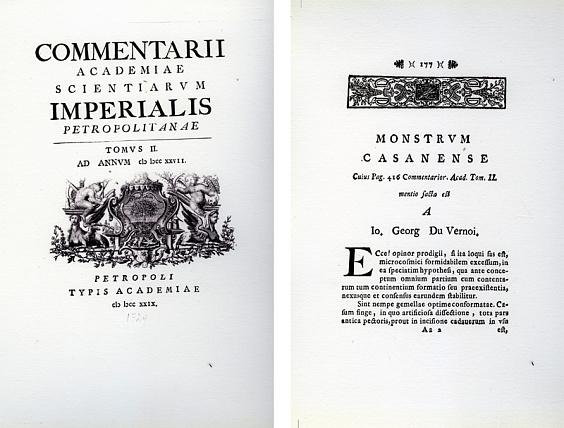

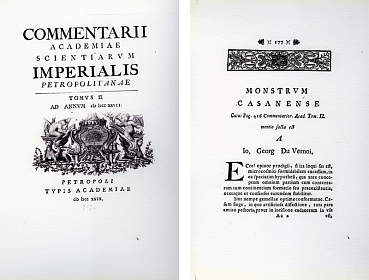

On June 27, 1727, Duvernoy made a presentation at a public assembly where he was “expounding the present condition of the anatomy of humans and animals <...> and made description of new things in the anatomy of an elephant which had been dissected in this city in the end of the last year.” Anatomical dissections in Russia did not attract that keen interest which they arose in the West. However, outcomes of Duvernoy’s researches were vividly discussed at the Conference and the Assembly of the Academy of Sciences, and starting of 1728, they were published at an academic journal Commentarii Academiae scientiarum Petropolitanae. In the 15 years of his work in Russia, the anatomist published about twenty articles in the “commentaries,” including 2 teratological ones.

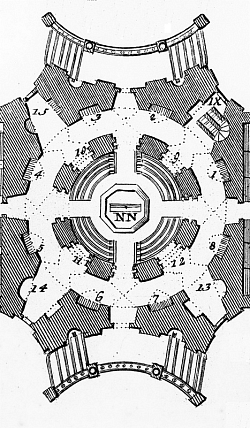

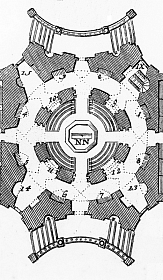

In 1728, the Anatomical Theatre was moved to the new edifice built for the Kunstkamera. Here, it was occupying a spacious round hall with an entrance directly from the Neva Embankment. J. Weitbrecht was appointed as J.G. Duvernoy’s Assistant and, gradually, all jobs on anatomical dissection of the corpses sent from the Police came over to him. In 1736, another anatomist from Germany started working at the Academy of Sciences. It was Johann Christian Wilde, who continued to work in the typical for Duvernoy area of comparative anatomical studies: observations on the anatomy of an elephant, research of a monster-hen and a hydrocephalus fetus. In 1741, he took over the affairs from Duvernoy who was returning to his motherland, but he had also left St. Petersburg later, in 1744.

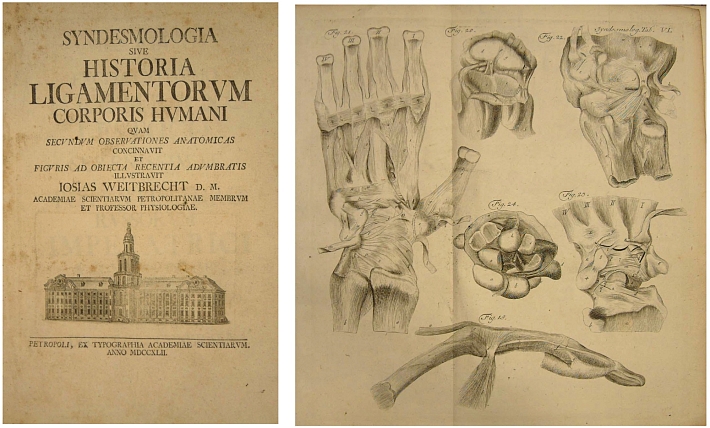

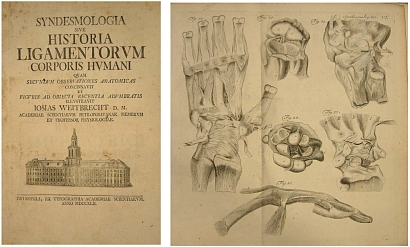

In 1731, Josias Weitbrecht was elected Academician of the Department of Physiology and in 1736, he got the Degree of Doctor of Medicine from the University of Konigsberg for his dissertation on the epidemics of “Petechial fever” which had occurred in St. Petersburg a year earlier. This job on the therapy of typhoid fever caused a major interest among physicians. However, the foremost Weitbrecht’s job was the first ever completed guide on syndesmology – a science of diarthroses, abarticulations, and bands of human skeleton published in Latin in St. Petersburg in 1742. Later on, it was published in France (1752) and in Germany (1779). Weitbrecht was elected foreign member of the Nuremberg Physics and Medical Society. His Syndesmology is still recognized as the foundation of the knowledge on bands. The Anatomical Theatre had been fruitfully operating this way up until the fire which had occurred in December 1747. After that, it had never returned into Kunstkamera’s walls and had to change its location 8 times within the next 60 years. For about 10 years, the Anatomical Theatre was operating in the Barons Stroganov’s house; for 2 years, it was located at the “Bohn’s Yard” and, later on, in the Miller’s House in the 5th Line of the Basil Island, and, lastly, for quite a long while (19 years) it remained in a separate wooden edifice built on the lawn in front of the main building of the Academy. Anatomists were replacing each other: A. Kaau-Boerhaave, A.P. Protasov, K. F. Wolf, P.A. Zagorsky; they all were unsatisfied with their working conditions and kept coming up with their own designs of the anatomical theatre reconstruction. In 1788, the theatre was placed in the new stone building of the Academy of Sciences. However, it was gradually losing its significance. Anatomical theatres had never got in Russia those general cultural functions which they had in the West: they were merely meant for scientific and educational purposes.